Defining personalities behind the success story

Over the past 150 years, strong personalities have steered the course of Continental’s history and thereby contributed significantly to the company’s success.

Whether as Directors General, or Chairman of the Executive Board or Supervisory Board – they have all shaped Continental in their own way. And, each in their own way, they all contributed to Continental successfully mastering the many crises and transformations in the company’s history.

Worthy of special mention here are the services of Moritz Magnus, Siegmund Seligmann, Willy Tischbein, Alfred Herrhausen, and Carl H. Hahn. They made far-sighted decisions and set the course successfully. Continental continues to be defined by their actions to this day.

In 1871, nine industrialists and private bankers joined forces to found Continental.

Standing out in particular among this group is Moritz Magnus who, as the main shareholder from 1874 onward, made a significant contribution to financing Continental. With ownership of the plots of land on Vahrenwalder Strasse in Hanover, Magnus was not only the most important founder, but also the one who took the initiative to reorganize Continental between 1874 and 1876.

While listed Continental shares first became available for stock exchange trading in 1897, the company’s shares remained comparatively evenly distributed among the local private bankers as major shareholders until the end of World War I. It took the inflation crisis to break down this structure, and more and more small shareholders acquired Continental shares.

What’s more, even in the early years following Continental’s founding, the far-sighted vision of Moritz Magnus paved the way for the company’s success, particularly with his bold and visionary investment in rubber – a raw material that held great potential for the future, but its material properties and market potential were, at the time, only known in very basic terms at best. In the subsequent years, Continental was thus able to tap into a lucrative future business area in the field of rubber products.

Moritz Magnus also hired Siegmund Seligmann in 1876. Together with Adolf Prinzhorn, he made a significant contribution to the rise of the company.

Within just a few years, Seligmann turned the battered Continental into a solidly profitable business enterprise: Shareholders, and later the workforce as well, thus benefited from the steady stream of new records set in distributed dividends. What’s more, Continental achieved this success even before entering the tire business, which only started gaining noteworthy momentum over the course of the 1890s. At first, the future viability of this product area was not nearly as secure as it might seem in retrospect: Bicycles and especially automobiles were still expensive luxury goods and far from being mass-market products back then.

Seligmann came up with numerous corporate strategy and policy measures aimed at driving Continental’s success forward. He acquired holdings in leading rubber companies and designed a forward-looking export strategy that was accompanied by a sophisticated strategy of innovation: Seligmann had the central laboratory expanded and acquired valuable tire patents at the right time. Unlike its competitors, which had almost exclusively developed into tire corporations, Continental’s product portfolio continued to grow under Seligmann’s tutelage.

Seligmann’s company policy was modern in many ways. It garnered all the more recognition as the company’s managers were confronted with some highly adverse economic and political conditions during these years: From the crisis in the bicycle industry at the turn of the last century to trade and customs conflicts, disputes with competitors, and the global financial crisis in 1908.

Seligmann himself held a large number of Continental shares and was therefore also an owner-manager. As such, he acted with corresponding sure-footedness toward the Supervisory Board. Among other things, he introduced a corporate social policy that significantly contributed to a high level of employee satisfaction and retention. In this way, he gained a favorable reputation among employees. The workforce headcount rose from just 216 when he started to 14,500 in 1925.

Willy Tischbein began his career as an internationally successful cyclist before completing a commercial apprenticeship and taking on responsibility for the tire business at Continental in 1894. Driven by his work in tire development and production, the company became an ever more professionally run organization.

Various challenges, such as the global economic crisis at the start of the 1930s, the emancipation of the workers’ movement and the transformation in the world of mobility did not prevent Willy Tischbein from undertaking fundamental changes in various areas of the company.

These included job performance appraisal procedures and performance-based remuneration along the lines of the Bedaux System emerging from the United States. Sales, distribution and marketing were also reorganized: A communications strategy directed toward broad customer and buyer groups and strategic sponsorship of sporting events made the “marketing genius”

Tischbein a pioneer in early sports marketing in Germany. He also represented Continental externally as a member of numerous professional societies, associations and institutions in the automotive and components industry.

Even though his innovations were initially the subject of heated debate, among employees in particular, they helped Continental to come through the global economic crisis relatively unscathed. In the second half of the 1920s, Continental developed into the dominant rubber company in Germany through various mergers and acquisitions. Tischbein was thus the “second father figure behind Continental’s long years of success.”

However, it was also Willy Tischbein who placed Continental at the services of National Socialism. In a series of communications, he expressly welcomed the new regime and its propaganda goals of economic and national greatness for Germany. The apex of Tischbein’s accommodation with the National Socialist regime was Adolf Hitler’s visit to the Continental booth at the International Motor Show Germany (IAA) in Berlin in May 1934. Tischbein also forced his contemporary Executive Board colleagues and the senior executives to join the Nazi Party.

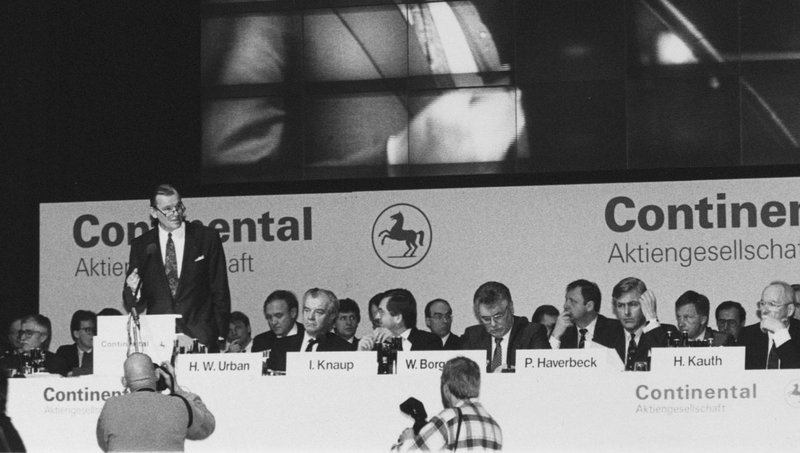

In subsequent years, two personalities in particular shaped Continental’s development: Alfred Herrhausen, member of the Executive Board of Deutsche Bank and Chairman of the Supervisory Board at Continental, and Carl H. Hahn, Chairman of the Executive Board at Continental. Although each had taken on different roles, their management styles were closely interwoven in many respects.

They guided the company through its biggest and longest crisis to date: the appreciation of the deutschmark’s value promoted the import of inexpensive tires, while at the same time the company struggled to overcome a technological deficit in steel belted tires as well as a macroeconomic downturn. This led to a massive collapse in demand. For the first time in its company’s history, Continental had to post deficit figures in the double-digit million range. Herrhausen and Hahn pursued their goal of leading Continental out of the crisis. They did so with a mix of industrial policy plans, which can even be described as desperate restructuring attempts that they stubbornly pursued, and a bold forward strategy combined with a tough reorganization policy.

Herrhausen also used his influence to take a stand and criticize the political situation. In his speech at the anniversary celebrations in 1971, he reflected on fundamental social policy issues against the background of the Federal Republic of Germany’s economic and social model.

Hahn openly pursued a tough reorganization approach without glossing over the company’s position. In 1972, Continental posted a balance sheet loss for the first time in its history, leading to a generational change on the Executive Board.

While Herrhausen considered selling off the loss-making tire business, Hahn prevented this, and instead the company opted to “take the bull by the horns”: With the acquisition of Uniroyal’s European business, Continental became an international company in 1979 that once again generated sales and profit growth in 1983, after a 12-year long struggle to survive.

Continental has a turbulent past – 150 years marked by crises that have shaped the company, and a unique success story. It is built on the actions of people who, through their various approaches and management qualities, ensured that Continental was able to keep pace with the competition and stayed fit for the future. Today, Continental is still crucially dependent on its employees, their diversity and the company’s unique working atmosphere. After all, they all have common goals: To overcome challenges together and continue to celebrate successes in the future.